When my son was a toddler, he couldn’t pronounce the letter “R.” Words like “river” were “wivuh” and “crab” became “cwab.” At the time, I thought these speech errors only made his chubby-cheeked baby-talk ramblings all the more endearing.

As he entered kindergarten, he learned to read and write, but not how to pronounce his “R’s.” My husband and I grew concerned, but his teacher assured us that the speech delay was age appropriate. So we didn’t worry — until he turned 7. When he was still saying “wun” and “ice cweam,” we decided to meet with a speech-language pathologist at his school.

A speech-language pathologist, or SLP, is a communications expert who is trained to evaluate and create solutions for speech and language disorders, as well as for swallowing and other motor functions related to communication. During my son’s assessment, the SLP’s trained ear was able to hear him form “R’s” in certain words. In other words, he was capable of making the sound and was well on his way to developing normal articulation without further intervention.

Common Speech Disorders in Young Children

Many children need speech therapy to address communication disorders. Each year, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), approximately 7% of U.S. children will demonstrate a disorder related to speech or communication. Disorders with no known cause are considered functional disorders, while organic disorders are the result of a diagnosed medical reason.

Speech sound disorders

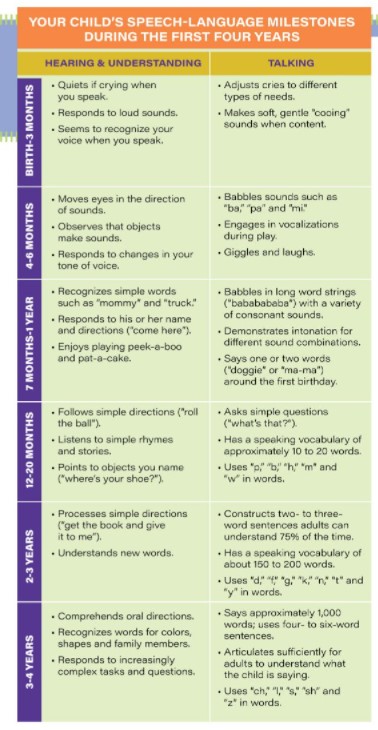

Just as there are age-appropriate milestones for motor skills like walking and running, speech skills also emerge on a predictable timeline. Some letter sounds, such as “m” or “b,” are easier for little lips to pronounce, while “r” or “th” develop later.

“When children are younger, substituting difficult sounds for easier ones is normal,” says Diana Letwinsky, a public school speech-language pathologist in Maryland. “Parents can support their child’s typical speech sound development by modeling slow, clear speech during play, while reading

together or during everyday activities.”

Children whose substitutions persist beyond the age that is developmentally appropriate may have a functional speech sound disorder, such as articulation and phonological disorders. Other less common speech sound disorders include dysarthria, a weakness of the muscles used for speaking, and childhood apraxia of speech, a motor disorder in which a disruption occurs in the pathways between the brain and the muscles used for making speech.

Receptive and expressive language disorders

Children with receptive language disorders struggle to understand the meanings of words. This struggle may impact their comprehension of oral language, making it harder for them to follow directions, participate in learning activities, or interact with their peers.

“A 2-year-old should be able to follow simple one- and two-step instructions. If we say, ‘Please get your shoes and put them on,’ they should be able to understand and comply,” says Linda Heller, a speech-language pathologist with Nyman Associates in Pennsylvania. A toddler who is unable to follow such instructions may have a receptive language disorder.

Children with expressive language disorder have trouble using language to communicate. This difficulty may impair their ability to express their needs. These kids often have more tantrums because they don’t have the language skills to express what they want, explains Heller. “As you can imagine, this can be very frustrating,” she says.

Social communication disorder

Social communication disorder is characterized by difficulties in the social aspects of communication—using language with other people.

“Some children struggle with social or nonverbal aspects of communication,” says Timothy Flynn, a school speech-language pathologist and owner of Forward Steps Therapy in Alexandria, Virginia. “For example, they may not be able to read facial expressions or body language or respond to social cues.”

Fluency disorder

Children with a fluency disorder have trouble speaking in a flowing, uninterrupted speech rhythm. They may include long pauses between words or say sounds rapidly, several times in a row, a condition known as stuttering. Cluttering, another fluency disorder, involves breaks in the typical flow of speech that seem to stem from disorganized speech planning, speaking too quickly or when children are uncertain about what they want to say. In contrast, a person who stutters usually knows precisely what he or she wants to say, but is temporarily unable to say it.

As both a speech pathologist and someone who stutters, Flynn is an expert on fluency disorders. “I can tell you that stuttering is still greatly misunderstood by most people,” he says. “Parents of children who stutter are often told to ‘wait and see.’ While many children do outgrow stuttering, there are several factors that speech pathologists consider to determine if intervention is warranted.”

Voice disorder

Problems with the sound and production of a child’s voice may indicate a voice disorder and should be evaluated by an otolaryngologist. Speech therapy with an SLP may be recommended as part of the child’s treatment plan.

Normal Development or Disorder?

How can you tell whether your child is developing on track or has a speech disorder requiring intervention?

“Your child’s pediatrician should be screening your child at each well visit to ensure that they are meeting their language milestones,” says Heller. “For example, a 2-year-old child should be able to say around 50 words. Remember, even animal sounds count as words.”

A pediatrician should also regularly test your child’s hearing. “Hearing is incredibly important for proper speech development,” says Flynn. “Frequent middle ear infections can build fluid in the ear that mimics how difficult it would be to hear underwater. Imagine if you were at a swimming pool and asked someone to try to tell you something while you were underwater. Naturally, you would not hear the speech sounds correctly, so you would reproduce them incorrectly.”

How an SLP Can Help

If you’re still uncertain about your child’s speech progress, it never hurts to seek out an assessment from a certified SLP. All children are eligible to seek services from their county’s infants and toddlers program or the SLP at your local public school. If they decide that speech therapy will be helpful, your child will begin meeting with the SLP on a regular basis.

According to Lindsay Lyons, senior speech-language pathologist with Sheppard Pratt School in Hunt Valley, speech therapy can be fun.

“I love to play and use age-appropriate toys to keep the students’ hands busy and increase their focus,” says Lyons. “My favorite go-to activities are the simplest activities, such as coloring, listening to music and overall play. Gross motor activities are also a favorite go-to for me. Going on the playground can increase a lot of language production.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2021 issue of Baltimore’s Child, a sister publication of Frederick’s Child.

Note: Children are unique individuals and develop at their own rate. Your child may not demonstrate all the skills outlined in the chart below by the end of the age range indicated here.

Sources: American Speech Language-Hearing Association; Children’s Hospital Colorado, Small Talk, LLC